Dogon Culture in Eastern Mali and Malian Religion

–Robin Edward Poulton aka Macky TALL

Dogon masks are the most wonderful in Africa. Each one has a secret, spiritual meaning. Dogons live in the beautiful-but-isolated cliff country on the Mali-Burkina borders – although many of their villages are now accessible and popular with tourists. Dogons worship one Creator, called Ama, to whom they pray with arms outstretched towards the heavens. They claim to be a Malinké population that emigrated away from the Niger River Valley some five hundred years ago, in order to avoid Islam. They chased out (and intermarried with) the Pygmy population then living in the cliffs, known as the Tellem. Many Dogons are very small. On the other hand the many Dogon language groups also trade with Fulani nomads, and some Dogons obviously have Fulani ancestors. Many Dogons speak two or three Dogon dialects as well as the languages of the Fulani and the Bambara.

Dogon Elders have great knowledge about the stars, and they are able to tell the future using their close relationship to Nature, and in particular to the white fox. The Dogons understood evolution long before Charles Darwin: while they venerate their human ancestors, they recognize as their most ancient ancestors the crocodiles and lizards and turtles who were alive 300 million years ago, in the era of the dinosaurs.

There are some interesting Dogon masks in the collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond.

Masks

Dogons make and dance the most spectacular masks in Africa. While many Dogon dances are also spectacles of entertainment presented for tourists, Dogon masks are made and used for their religious and burial rituals. While masks represent human and animal aspects of Dogon life (like the rabbit-hare and mountain goat seen in the left photo, and the famous kanaga antelope mask that has become the symbol of Dogon Country), their deeper meanings are secret. Masks are only worn by members of the Awa, a secret spiritual association masquerades lead the souls of the deceased to their final resting place. The death anniversary religious ceremonies, the Dama, take place every few years to honor male and female elders who have died since the last Dama. The Sigui ancestor-celebration festival is danced only once every sixty years.

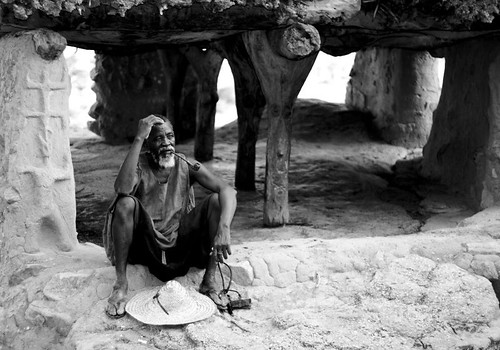

Toguna

The toguna is the Dogon meeting house for older men. The roof is supported by pillars made of stones, or tree-trucks which may be elaborately carved. To enter the meeting house, you have to crawl; while elders may sit for long periods in the cool shade of the meeting room, it is not possible to stand. Here in the toguna, they discuss the affairs of the community, smoke their pipes, gossip or maintain the silence that betokens wisdom… and this is also where the Elders take decisions that they transmit to the hogon or – depending on the age and mental acuity of the village chief (who lives apart and is considered a ‘living ancestor’) transmit to the village the decisions they have received from the hogon. Debates can become animated. The toguna has a characteristic low-but-thick roof, covered with branches (often used for storing animal fodder – so that the roof gets smaller as the dry season advances). Anyone who rises to his feet in excitement or in anger, hits his head on the beams of the toguna and is quickly returned to a state of calm.

Malian Monotheism

All Dogons interact with the Fulani herders, and many of them speak some Pular (the language of the herders: the herders trade milk for the millet and onions of the Dogons. This is a classic state of mutual economic dependency that leads to a special relationship between the two ethnic groups. It may have begin with the Dogon eastward migration. Dogons appear to have been a group of Malinké clans fleeing the civil wars that came with the erratic periods of disintegration that characterized the Mali and Soghai Empire between 1400 and 1600, and also fleeing the imposition of Islam. To cross the Niger River, they needed the Bozo fishermen, who were the allies of the Fulani (who cross the river each dry season to find fodder for their cattle) … and they needed the Fulani to guide them and sell them milk.

The Fulani creation myth seems to provide a perfect example of how the peoples of Mali envision life and the creation of the human race. It translates the depth of African spiritual beliefs, so different from the Jewish creation myth of the Garden of Eden. The Jews had a tribal, patriarchal social structure dominated by men like Adam and Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.[1] West Africans had a matriarchal social structure that still infuses daily life and spirituality.

In Africa, spirituality infuses the whole of life. There is no separate concept of ‘religion’, for spirituality is in everything and it comes from our Supreme Creator – Guéno in the pular[2]. Everything about Malian daily life and the relationships between people is rooted in spirituality. The Toucouleur are very conscious of their nomadic and Fulani origins. Their pride and wealth is stored in cattle. They are less mindful of the health and milk production of their animals, than of the size of their herd. Big men have big herds. There is prestige in numbers. Cows are naturally at the root of the creation myth of the Ba and Ka and the Tall:[3]

IN THE BEGINNING there was the cow.

Guéno the Eternal first created the cow. Next he created woman. Finally Guéno created the Fulani. He placed the woman behind the cow. He placed the Fulani behind the woman. Thus was created the cowboy. Thus God created the sacred trinity of the cattle herder. Glory be to the Creator of all things, to Him who created chaos and light, the fertile egg and the empty vacuum. From a drop of milk He created the universe. From the act of milking He created speech. Nomad speech is a long river of milk spreading across the desert, meandering through the forests, telling and re-telling the incredible adventure of the Fulani.

It all began at the Beginning of Time. It was there, in the far Eastern burning desert, in the ancient lands of the Pharaohs, that the Hebrew Bouitoring met a woman called Ba Diou Mangou. The White Man saw that the Black Woman was beautiful, and the Black Woman saw that the White Man was good. The latter demanded the hand of the former, and Guéno accepted.[4]

Milk has huge importance in the Fulani and Toucouleur tradition, and throughout West Africa. Some legends state that ‘Guéno created the world from a drop of milk.’ If cow’s milk has symbolic importance, how much more mystical is the role of mother’s milk!

The proverb says, ‘You are what you eat.’ What does the newborn first eat, if not his mother’s milk? Life is therefore milk, and milk gives life and symbolizes life. When you visit a Malian household, the first thing you will receive is a cup of water, as a sign of greeting and friendship, and to refresh the traveler after his journey. However, when you arrive at a Fulani encampment a young girl will immediately bring a calabash filled with milk.

I confess that this tradition sometimes causes me problems. What I fear most of all in rural Africa, is brucellosis. Known as ‘undulating fever’ to veterinarians and as ‘abortion fever’ to cattle ranchers, this disease is endemic to West Africa. Malians call it ‘Fulani fever’. The brucella bacterium that causes the fever – and which causes cattle and sheep and goats to abort their fetuses – is sensitive to antibiotics in vitro; but in practice the disease cannot be cured once it enters the body. I can handle occasional bouts of malaria and dysentery, but I really want to avoid the daily fevers of that debilitating disease brucellosis.

Milk is sacred when it comes from the mother. Any two children who have been fed at the same breast become ‘milk brothers’ or ‘milk sisters’ and the ties (and taboos) between them are as strong as if they had been born from the same womb. Milk siblings cannot marry. No matter who your father was, mother’s milk binds you as tightly as the bond of procreation.

It is significant, in passing, to note that the word ba in the Bambara language which has become the lingua franca of modern Mali, means ‘mother’. The founding woman of the Fulani and Toucouleur therefore carried a name that refers both to her soul and to her motherhood. Motherhood is considered divine in West African culture. The most important African title is not President, or King, or Tounka or Mansa, it is ‘Mother’. In the sigui procession of Dogon masks that honors the Ancestors once every 60 years, it is the mask of the First Fulani Woman that leads the procession. Eve takes precedence over Adam in traditional African culture.

I must complete the historical record of the Toucouleur. Tekrur is an ancient name, going back several thousand years to the ancient migrations of the Toucouleur to the Senegal River. The name was revived in the kingdom of Tekrur which flourished 9th to 13th centuries as a Soninké kingdom, founded by the Dia (Diagouraga) clan that survived on the left bank of the Senegal River alongside Ghana (or under its tutelage) until a new empire called Mali absorbed the region. The name was revived by the Toucouleur warlord Koli Tinguella who founded the Fulani-speaking Dényankobé dynasty in the sixteenth century. This Tekrur kingdom lasted 1559-1776, when it was taken over as a Muslim theocracy by the Torodo clan.

Then in the 1800s a new Toucouleur kingdom arose, known as the Segou Tekrur Empire, and led by the Islamic conqueror Cheikh Oumar Tall.[5] Tall is – of course – my Malian ancestor, although he might be surprised by the whiteness of my Scottish complexion!

Segou had resisted until this point the imported religion of Islam, which arrived in Mali during the 800s with the trading camel caravans that brought salt to Timbuktu and carried Malian gold back to Morocco and the Mediterranean. In the middle ages, one third of Europe’s gold came from the Mali Empire. But while the western areas of the empire progressively accepted Islam over the centuries, Segou did not. The Tall invasion brought to Segou the Tijania – a version of Islamic worship and law that developed in Morocco and was adopted by the Tall clan.

—-

Segou today is a very Islamic city. Sister City of Richmond, Virginia, in the American Bible Belt, Segou now houses the head of the Tijania and a whole range of other important religious Muslim leaders and marabouts. It is a Malian religious city with almost as many mosques as Richmond has churches.

[1] To understand the Middle East today and the Old Testament of yesteryear, I recommend a wonderful novel by Anita Diamant, called The Red Tent.

[2] pronounce Gay-no. In the French transliteration, the ‘u’ serves to make a hard ‘G’.

[3] Ba and Ka are the two spirits of Man: the life force and the soul (related to the Jewish Kaba); Tall is the Fulani Toucouleur clan into which I was adopted.

[4] Monenembo

[5] Wikpedia offers the following variety of spellings for his name: El Hadj Umar Tall, also Umar Tal,Umar Taal “Umar Futi”, al-Hajj Umar ibn Sa’id Tal, or el-Hadj Omar ibn Sa’id Tal, (ca. 1797 – 1864). I have kept the French spelling that Malians use. El Haj is a title that refers to his pilgrimage to Mecca.

One response to “Dogon Culture and Malian Religion”

[…] Dogon Culture and Malian Religion | … – Dogon Culture in Eastern Mali and Malian Religion-Robin Edward Poulton aka Macky TALL . Dogon masks are the most wonderful in Africa. Each one has a secret, … […]